(Dis)Orienting the Underground (Part 2): Dancing with ghosts

Nouveau-maharajas and global citizens

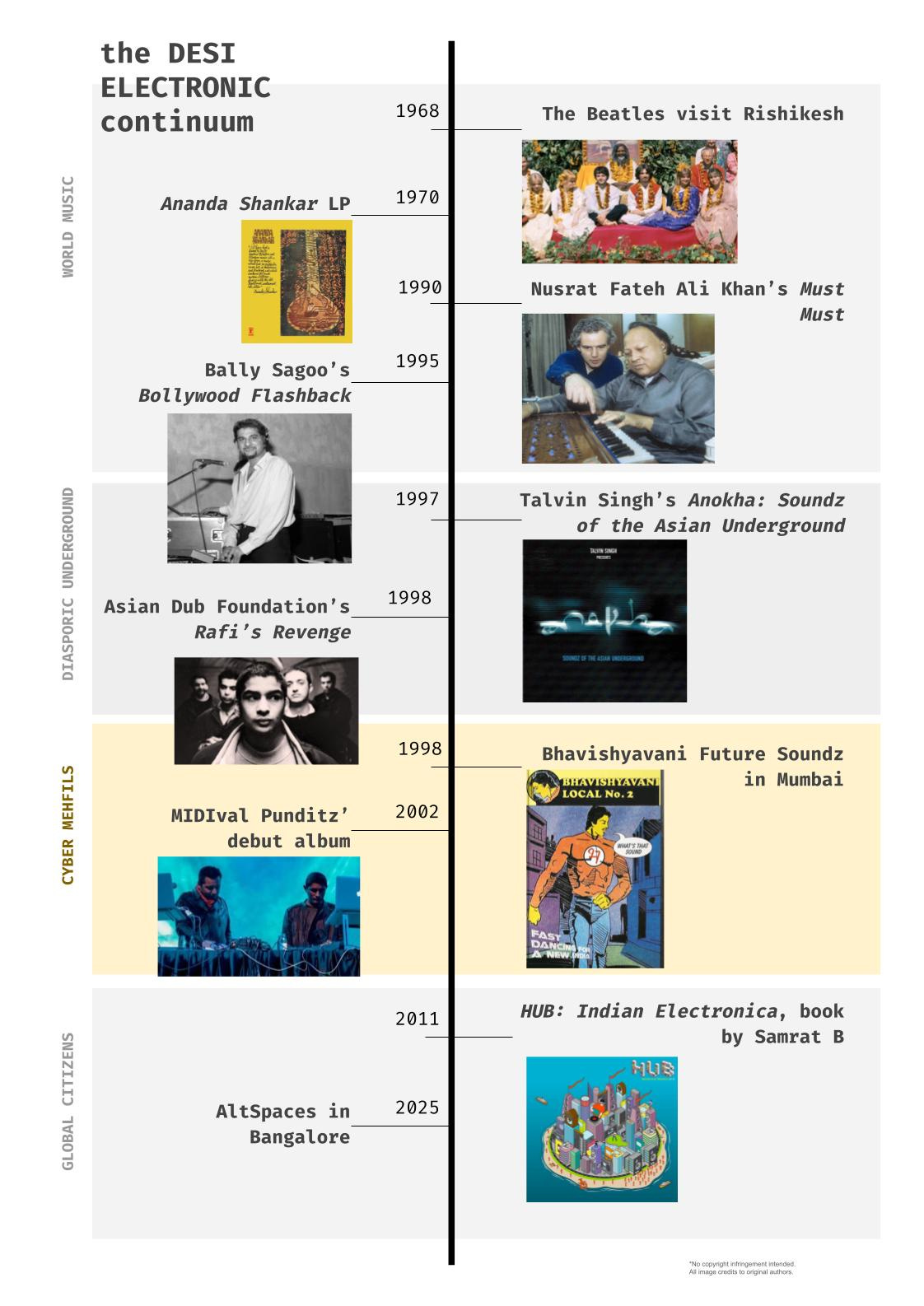

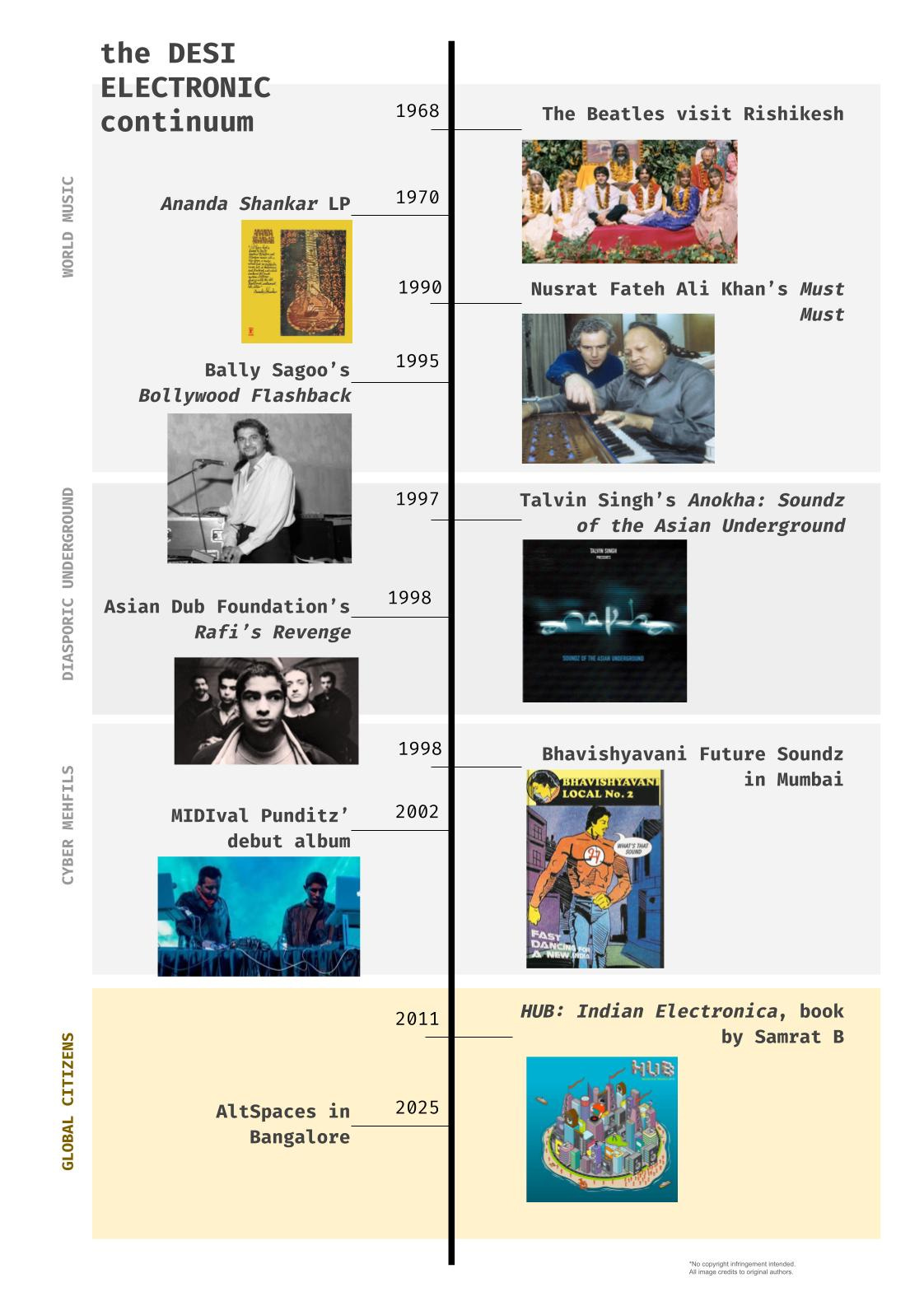

This is the second of a two-part essay exploring the cultural politics of electronic fusion music that combines traditional sounds from the Indian subcontinent with Western production. The two parts span its origins in 1990’s World Music and the diasporic experiments of the Asian Underground, back to the homeland with MIDIval Punditz’ cyber mehfils in Delhi, and finally to the present day in Bangalore at gigs hosted by Alt.Spaces. What I have tentatively called the ‘desi electronic continuum’ has evolved between Western influence and South Asian identity, and between futurism and heritage. Throughout this lineage, fusion music has promised spiritual transcendence, subcultural identity, and artistic rebellion. Fusion genres have often been framed as inherently progressive due to their hybrid quality. But this series asks a harder question: does desi fusion music reproduce the very inequalities—between West and East, modernity and tradition, elite and mass—that it claims to transcend?

In the first part of this series, we explored how Indian fusion music emerged out of global circuits of exoticism and diaspora. Indian fusion music in the West was composed of a fundamental distinction between ‘modern’ sounds of beats and basslines with ‘traditional’ sounds of Indian music. Also related to this opposition are loaded terms like ‘futuristic’ and ‘heritage’, ‘Western’ and ‘Indian’, and so on. But these are not neat oppositions and sometimes they complicate each other.

After the 90s, the continuum of Indian electronic fusion music returned home, repatriated and rebranded by a new class of Indian elites. The subcontinental musicians inherit the same tensions and dangers of self-exoticisation that the Asian Underground were familiar with. But even though its aesthetics remain similar, the continuum has been wrenched out of a specific social and political contexts and into another. The diaspora felt assimilation to be a threat to their idea of heritage, shared contexts and Indian 'essences'. But now after its import into India by and for elite urban youth culture, those politics have been lost— or transformed— in translation.

Cyber mehfils and the nouveau maharajas

Back in the homeland, Talvin Singh's mentee and the biggest proponent of Indian fusion electronic music was MIDIval Punditz. MIDIval Punditz is inseparable from its context of the post-liberalisation era. The 90's and early 2000's was marked by the fantasy of an Incredible India coming into its own, brushing off the shackles of Nehruvian socialism, and taking its place on the world stage. The first generation of liberalisation's children were those that disproportionately benefited from this idea of an emergent India, and composed mostly of a privileged section of urban, Savarna millennials.

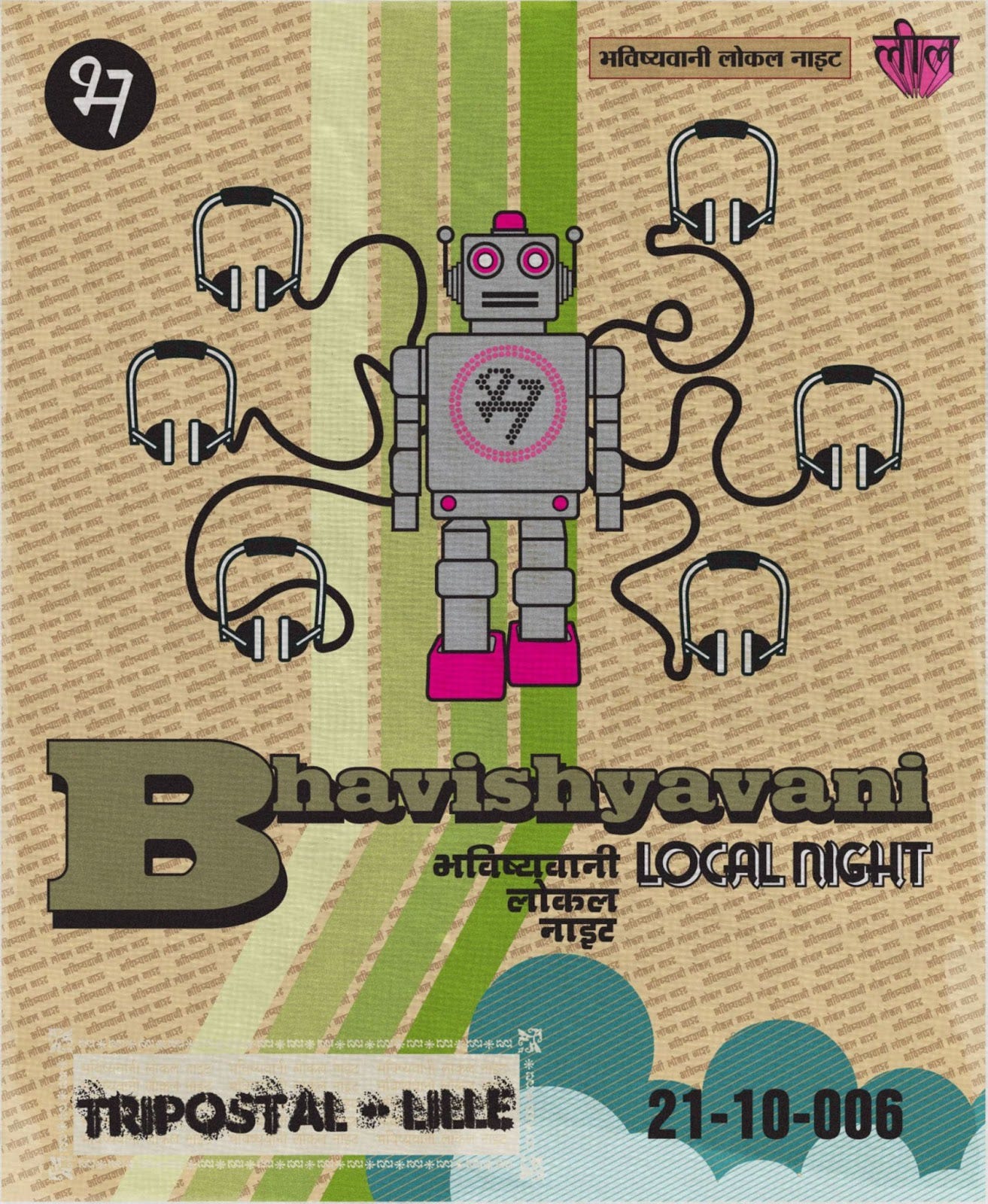

In an analysis of the 'cyber mehfils' organised by MIDIval Punditz in Delhi in the 2000's, Dhiraj Murthy (2010) reveals this genre to be at least possibly political. Even though many in the audience described the cyber mehfils as nothing more than ludic parties for Delhi's bored elites, the artists he interviewed in Delhi unanimously believed that the music they were creating was political. They presented their music as:

responding to a loss or disconnection of the modern metropolitan Indian from national tradition and a sense of Indian-ness, and

a celebration of domestic culture being empowered and recognised on the global stage.

For these urban elites that Murthy describes as 'nouveau maharajas', fusion music like Indian electronic music is emblematic of an emergent, modern India that still keeps in touch with its heritage and roots. There is pride in being represented abroad through 'our' music. Of course, disguised in the empowerment is still the need for the West's approval and patronage. One of Murthy's informants revealingly said that they “feel proud that West is buying music from the East".

This, of course, completely erases what Part 1 of this series established— that this music was diasporic in origin, and its politics were completely different. As Murthy points out, those in the subcontinent see their diasporic counterparts as 'not quite' Indian. This is only until there is something to claim as a national product — not unlike when NASA astronauts or American rappers are claimed to have been Indian all along.

By this logic, 'authenticity' is found not in who made it and in what context, but merely because of the music's usage of traditional sounds and instruments. In Murthy's paper, a quote from an unnamed interviewed journalist in Delhi stands out:

“A lot of my friends like the whole idea of beats with the sitar and the tabla. It’s kind of an India which is saying that we are important . . . [it represents] the idea that we have arrived, this is the global music. It’s not just us listening, it’s the whole world listening, and it’s got the sitar, the tabla—our instruments.”

This is a singular, monolithic ‘we’, as if all Indians could be represented by ‘our’ instruments. All other sounds are erased in favour of a singular style and tradition. As are all other identities that do not conform to a particular conception of what it means to be Indian. MIDIval Punditz' music assumes an inherent essence of Indian-ness that is shared by all Indians. Gaurav Raina of MIDIval Punditz said in a personal interview with Murthy that:

“Being Indian is the basic thing which ties it all together. . . . everywhere in India you go, the basic feeling or the basic sense of belonging everybody has is similar.”

In part one of this series, we saw how World Music allowed white liberal culture, alienated in globalised modernity, to appropriate the authenticity of the exotic. This authenticity is captured by reducing the local culture to exotic tokens of a supposedly universal, basic ‘essence’— not unlike the ‘basic feeling’ of Indianness that Gaurav Raina describes.

Murthy also quotes Gaurav Raina in an interview with the magazine Krich in 2005, clearly showing that their music is envisioned as a response to globalisation: “For people frustrated with corporate, globalized reality, Indian music is one of the places to turn”. MIDIval Punditz’ opposition of the authentic tradition with 'corporate, globalized reality' is itself derived from the same fears and alienation behind Western exoticization of India.

The hauntology of Indo-futurism

Another dimension of the continuum is its relationship with visual and sonic futurism. Ordinarily, ‘Indian’ elements are associated with traditional heritage from a bygone, ancient civilisation of the past, while the ‘Western’ are conflated with modernity, efficiency, technology and the future.

But these categories are slippery and artists deliberately play with them to create whole new imaginary worlds. The past becomes inspiration for the future, and modernity becomes located in tradition.

Afrofuturist thinker Kodwo Eshun's notion of an Advanced Rhythmic Technology (ART) includes classical Hindustani and Carnatic music, and shows how complex technology and knowledge can be recovered from bygone eras and traditions. These ‘technologies’ reveal sophisticated advancements by cultures that have now been marginalised by global (white) culture, and confined to ‘tradition’ and ‘heritage’.

Indo-futurism uses speculative fiction and fantasy to look back at shared culture and heritage. In doing so, it can unearth radical imaginations and possibilities of Indian-ness in a future world (to illustrate this movement beyond the musical, you can -take - your - pick from Indofuturistic aesthetics in art today). Like Afrofuturism, Indo-futurism is an aesthetic movement which displaces the present with haunting memories of imagined futures, i.e. memories of what-could-have-been.

But these haunting possibilities are not only the obvious postcolonial question of what-could-have-been (if colonisation did not happen). To imagine a radically different future means to reckon with the present status quo— of social inequalities in class, caste, gender, sexuality. In a Master’s dissertation, one Kyle Schirmann of Columbia University identifies a queer futurism in MIDIval Punditz’ track Khayaal, which is in a contemporary ghazal form. The ghazal form is well-known for 'ambiguity of gender and consequent homoerotic undertones'. Queerness essentially rejects the here-and-now status quo and insists on the possibility for another world that defies binaries and boundaries. Thus,

“The ghazal in “Khayaal” may thus be read as a requiem which traces an ultimately unrealized homoeroticism of the past. [...] The pleasure of listening to “Khayaal” comes from its trajectory of shared, collective struggle, an arc which connects the past and the present before mobilizing a politics of hope as it launches toward the future. It forgives the frustration of a future which never came to pass by suggesting that its possibility lies beyond some eventual horizon”

Schirmann even suggests that this "electronica perhaps fills a cultural void left by the exasperation [with] the left in Indian politics.” This is similar to how Kodwo Eshun described a fatigue with futurity and political imagination among African intellectuals in the late nineteenth century, and Mark Fisher described Alt-J and Britpop music as pastiche and nostalgia to cover up the failure of British working class politics.

‘Underground’ is a contentious term when used to describe dance music scenes in India. One could argue that these electronic scenes are ‘underground’ in the sense they are alternatives to mainstream culture industries like Bollywood. They are also short-lived due to the lack of support infrastructure and favourable conditions— nightlife IPs that are not monopolistic or a race to the bottom in a service sense are a rarity. And social dissent does sometimes find its way into electronica, even if tangentially. Schirmann also offers an example of Imaginary Parrots Cheebay (2012) which is a song by Karachi’s Dynoman, of the band Forever South, which begins with snippets of conversation about parents and secret weddings. Forever South joined homegrown electronic collectives like Karachi Detour Rampage in a then-promising underground music scene that was soon to come of age, but quickly dissipated.

What makes scenes plausibly ‘underground’ here is also their moral persecution by the dominant, conservative social order. Club culture is closely associated with drugs, with many events organised without permits and risking police confrontation. In this cat-and-mouse chase, promoters are often complicit, tipping off competitors to police who needed to meet monthly quotas.

Still, even if nouveau maharajas are ‘exasperated’ with politics and governance, the jury is still out on if this music actually critiques any status quo. At the end of the day, this is music culture consumed by a privileged elite who are fairly alienated from the realities of the country.

Global citizens and the burden of inheritance

All this context shows us the diverse and complicated tapestry we are descendants of. There is now a rich recent history of homgerown artists working between Indian and Western electronic music. Samrat Bharadwaj's now outdated book HUB: Indian Electronica 2010 is a good overview of a scene we take for granted.

While building AltSpaces, Shivhari acknowledges our indebtedness often with an Isaac Newton quote— "I only see further because I stand on the shoulders of giants." But we inherit not just the sonic textures of the continuum, but its fundamental tensions and identity politics.

Alt.Spaces is one of many in Indian electronic music, and is haunted by the same internal tensions that blighted World Music. Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan had to watch as they diluted eloquent Sufi mythology into pop hits— he wanted to intervene but was forced to 'compromise'. Shivhari is also wary of this pitfall, of merely mixing loops and chopped-up vocals. In his words, this is not "cheesy" "bastardisation" to be "sold as Indian". He is deliberate and intentional in his crate-digging, and he gives his classical selections the space and time in a mix they deserve to be appreciated.

And what of the nouveau-maharajas, how have they evolved since the times of cyber mehfils? As Shivhari agrees, MIDIval Punditz broke through at a time when emergent India was staking its claim on the world stage. But now we are already global(ised) citizens, who have more in common with hipsters in Berlin than with the country’s masses.

For us global citizens, who 'just happen to be in India', being modern is a given and we have internalised the white man's gaze. We see in the mirror the pale mask of homogeneity, and want to go native (again). Shivhari is reticent to admit, but his music does convey "a sense of home" to people, and they may feel comfort in a fantasy of Indian-ness. But we are not ‘re’- connecting with heritage, as I suggested, because as Shivhari pointed out we were never connected with it in the first place.

But Shivhari wants to build a community without identity politics— which he sees as divisive. Identity performance can empower people, but sometimes it is better to be inclusive, to welcome everyone— "Music should not be the place where we fight wars over identity".

Shivhari, who stands on MIDIval Punditz' shoulders, rejects their claim that there is some 'basic' essence of Indian-ness that the music appeals to. That optimistic idea of India and Indianness on the global stage has changed. Superpower-by-20xx projects have failed spectacularly, Internet culture has turned on India and revealed the country's shortcomings, and any feel-good sense of patriotism has turned sour. Internally, we are more aware of social divisions than ever. There cannot be any misconceptions that we are culturally or spiritually unified. As Shivhari says, "India is a useful political construct and an abstraction but it has a limit ... there is no single reality here".

If not a sense of home or national heritage, Shivhari believes in his music’s universal spiritual appeal, cutting across identities and boundaries, purely based on its experiential sonic quality. As he puts it, white foreigners in the Pushkar desert having a spiritual experience to Rajasthani folk classical music enjoy it just the same as us despite having less context. Beyond culture and identity, this is 'ancient', 'tribal' music that appeals to some deep rooted universal humanity.

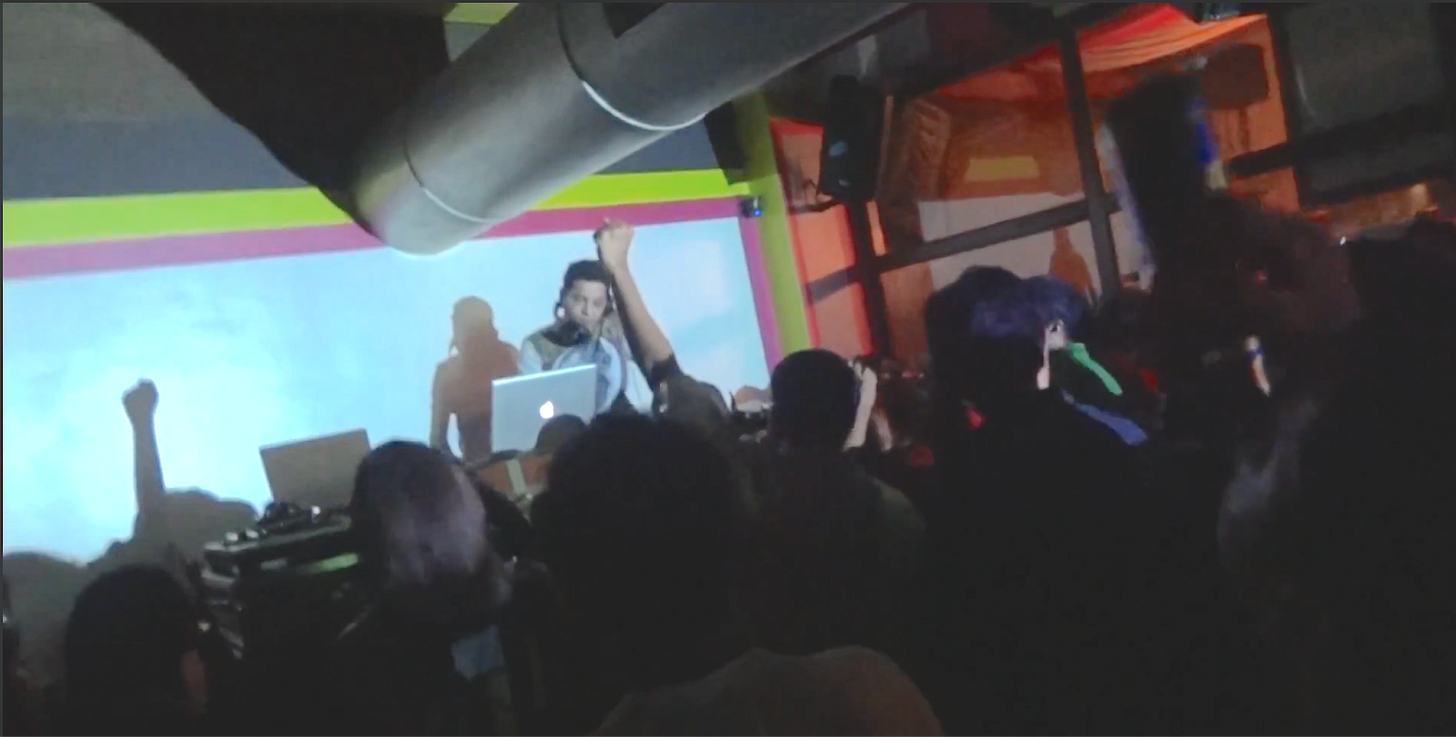

His ethos is of love and compassion, of no hierarchy between the DJ and the dancefloor. Shivhari knows intimately the importance of these experiences to people's lives— and so he treats someone's feedback and attention with utmost seriousness and responsibility. He aspires to recreate the togetherness and spirituality of Goa psytrance scenes, which taught him how through music:

"You can alleviate suffering, you can be in the here and now, you can feel part of a larger community… Dancing has been in our genes for 100,000 years... Dancing activates something fundamental and primitive, a sense of feeling as part of a tribe… The dancefloor provides you what you need."

(above) Vridian's recent release Days of Paradiso which ripped up the dancefloor at AltSpaces was made as a homage to Goa trance that he never got to experience (imagined memories that could-have-been) (source). Shivhari similarly also said the Goa scene is a big inspiration for his vision of community ethos. The irony should not be forgotten that Goa trance was a hybrid product made in an enclave of white culture in India. Despite efforts to gatekeep it from Indian tourists, that enclave declined and has now disappeared after the pandemic.

Shivhari's vision and ideology— of authenticity through ‘primitive’ spirituality— clearly echoes those in the continuum before him. He may hope to transcend cultural identity politics, but his music cannot escape its inherited context.

The same internal conflict follows us to the present. By celebrating our own heritage as ‘spiritual’, ‘authentic’, ‘tribal’, are we perpetuating the same self-exoticisation? Are we denying our music their critical and revolutionary potential? World Music was marketed as universally spiritual and authentic, consumed by white people as an alternative and response to the authenticity of Black music. Is it possible that fusion music in India plays a similar function for urban Savarna culture today, which is similarly threatened by the rise of Desi Hip Hop and the threat of mass access to dance music?

In any case, Shivhari knows his “movement” is “not there yet”. But it is growing, one disciple at a time. Uncles and aunties at weddings, coffee and burger shop ravers, tech bros, are all waiting to be onboarded, and positive responses from unexpected sources gives him courage.

No Home to Return to?

Today, the desi electronic continuum is going strong and spans genres. Cutting-edge contemporary dance from Baalti shares the limelight with retro-pastiche from Glass Beams or Khruangbin. What these examples all share is some contact of Western technology with vernacular languages, aesthetics or cultures, usually mediated by diaspora. These points of contact are made in the cause of 'hybridity', on the delicate fault lines between neo-colonialism and self-exoticisation.

If Asian Dub Foundation was a politicised voice of international diaspora, then experimental, fusion club music like that nurtured at Alt Spaces is the sound of the intra-national, inter-state diaspora. For the global diaspora, the fantasy of India was stuck in time, protected. For the elite internal diaspora, the fantasy of emerging, superpower India has long collapsed in front of our eyes. Unlike for the global diaspora, for us there is no 'back home' to nostalgise about, and with global recession impending there is no ‘outside’ to escape into. It may be too generous to think that what haunts the ‘nouveau-maharajas’ at Alt.Spaces is the unrealised possibilities of a modern, liberal India. In truth, what haunts us is probably our personal futures that could-have-been— our lives as foreign expats in the West, finally being cultural minorities who can feign angst without question.

Today’s Indian electronic music is no longer about representing India to the world. It’s about finding fragments of self in a culture whose past is increasingly volatile and weaponised. There is no spiritual unity left to reclaim, only pre-digested nostalgia and broken, haunting inheritances. Our future and past need to be synthesised out of the flotsam of failed nation-building projects. The scene may not escape the structures it inherits—but on the dancefloor, something else becomes possible: not a return to home, but a moment of shared estrangement.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Shivhari Shankar for his time and patience with my questions. Thanks also to reviewers: Pranav Manie, Apoorv Somanchi, Sanjana Sheth and others.

No copyright infringement intended. All material credits to the original authors.

References

Banerjea, Koushik (2000), “Sounds of Whose Underground? The Fine Tuning of Diaspora in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Theory, culture & society, 17(3), 64–79.

Gopinath, Gayatri (2005), Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures, Duke University Press,

Hasan, Rafeeq (2001), “The Dialectic of the Dance: On Talvin Singh’s ‘Anokha,’” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 32(4).

Murthy, Dhiraj (2010), “Nationalism Remixed? The Politics of Cultural Flows between the South Asian Diaspora and ‘Homeland,’” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(8), 1412–30.

Schirmann, Kyle (2015), “Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica,” Master’s Thesis, New York: Columbia University.

Sharma, Ashwini (1997), “Sounds Oriental: The (Im)Possibility of Theorizing Asian Musical Cultures,” in Dis-Orienting Rhythms: The Politics of the New Asian Dance Music, ed. Sanjay Sharma, John Hutnyk, and Ashwini Sharma, London; New Jersey: Zed Books