(Dis)Orienting the Underground (Part 1): The desi electronic continuum

World Music, diaspora, and self-exoticisation

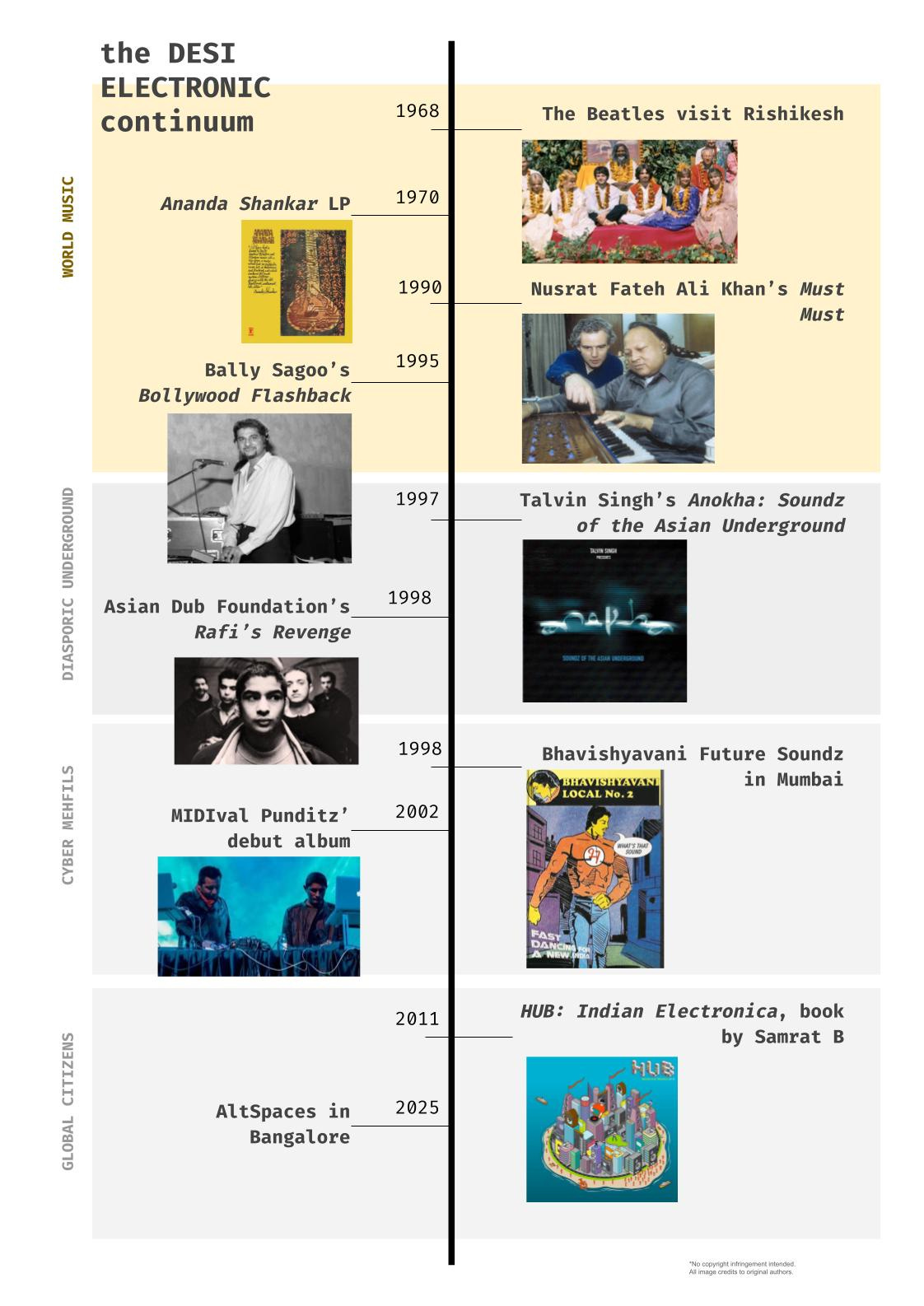

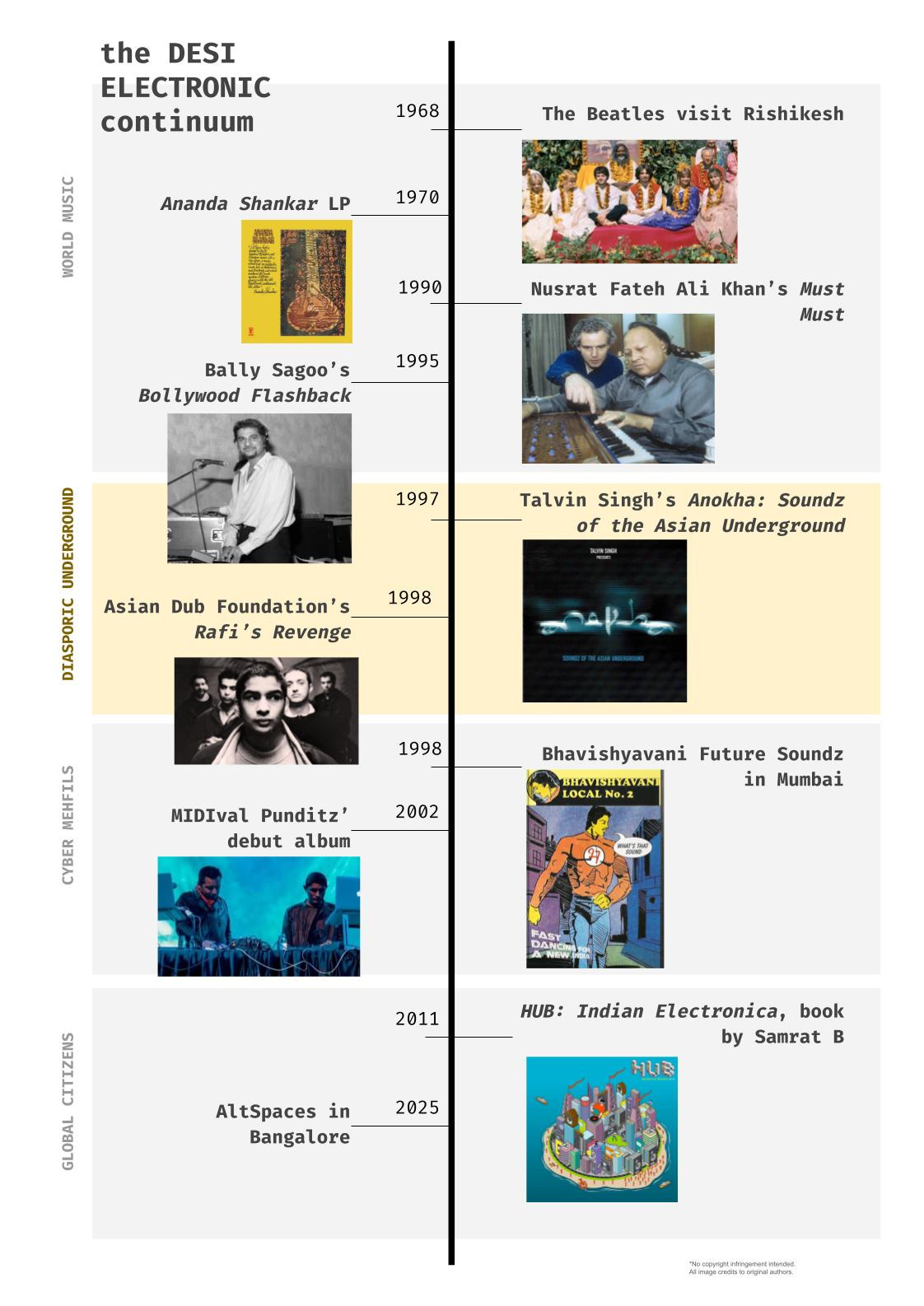

This is the first of a two-part essay exploring the cultural politics of electronic fusion music that combines traditional sounds from the Indian subcontinent with Western production. The two parts span its origins in 1990’s World Music and the diasporic experiments of the Asian Underground, back to the homeland with MIDIval Punditz’ cyber mehfils in Delhi, and finally to the present day in Bangalore at gigs hosted by Alt.Spaces. What I have tentatively called the ‘desi electronic continuum’ has evolved between Western influence and South Asian identity, and between futurism and heritage. Throughout this lineage, fusion music has promised spiritual transcendence, subcultural identity, and artistic rebellion. Fusion genres have often been framed as inherently progressive due to their hybrid quality. But this series asks a harder question: does desi fusion music reproduce the very inequalities—between West and East, modernity and tradition, elite and mass—that it claims to transcend?

Part one traces the global and diasporic roots of the genre, examining how the South Asian identity was curated and sold in the West. Part two turns to its repatriation to elite youth cultures in the subcontinent, and considers how artists today inherit this complex legacy.

It is a given that Bangalore is a melting pot for young, ambitious migrants. Despite political and social backlash, regional diasporas have reshaped the identity of the city. This shift is visible in its music scenes too. On a Sunday night in February when the weather recalls Mumbai's, Hindi is spoken conspicuously on Ulsoor’s main roads. Inside Aqua at The Park, Alt.Spaces' gig is as eclectic and inspiring as ever, but the crowd is not indigenous. In the niches of the city, Shivhari Shankar is building a diasporic community around music that crosses geographical and historical boundaries.

AltSpaces hosts a highly educated crowd that knows when to stroke their chins (for Mahaalaxmi's ambient dub) and when to go airborne (for Vridian's too-techno-to-be-house). A cover of Charanjit Singh's now-anthemic Raga Bhairav (1985) elicited a manic response that contrasted sharply with the listless crowd at Magnetic Fields in December, where the track was played by at least four foreign DJs. Alt.Spaces is premised on Shivhari Shankar's vision and taste. He is clear that he is "building a movement", but he is careful to avoid the ego and clout-chasing that can come with being at the vanguard. His music is difficult to name, and after much deliberation he has arrived awkwardly at a functional label: "Indian classical electronic fusion music". It’s no wonder that his community WhatsApp group is ambivalently named “Asian Underground / Indian Fusion Revival.”

Alt.Spaces is one of many present day enclaves of a rich tradition these names refer to. This article explores the complex politics, histories, and geographies of this slippery genre—or rather, this continuum of genres and scenes.

Exotic origins in the Third World (Music)

The continuum of genres about to be described is essentially a history of hybrids— between Indian (or South Asian) music with Western electronic music. When I say 'continuum', it is with direct reference to Simon Reynolds' term 'hardcore continuum', which describes a fairly distinct and linear cultural evolution in British electronic scenes beginning with rave and ending(?) with dubstep. Our continuum is anything but clear-cut.

Today, from food to fashion and back, marketingspeak words like 'fusion' and 'glocal' have become ubiquitous, alongside related epithets like ‘ethnic’, ‘tropical’, ‘folk’ and ‘tribal’. Despite being cliched through overuse, 'hybridity' is still celebrated as if it is inherently progressive and ground-breaking.

But hybridity is fraught with ideological tension. No example captures this quite like so-called World Music. Invented as a genre to sell firstly to the Western, white, affluent music consumer in the late 80's and 90's, World Music celebrated the authenticity of exotic non-Western cultures.

Exoticisation had always accompanied the coloniser’s fascination with the savage’s culture. With modernity came homogeneity and loss of sense of tradition and heritage, driving desires for a fantasy of ‘authentic’ Oriental culture. The result is an extractivist imperialism that stretches from pre-colonial trade for exotic goods and into modernity with the appropriation of spiritual practices like yoga.

But World Music specifically is motivated by a deeper social insecurity in white Western society that emerges after 1960’s counterculture and the American civil rights movement. The series of watershed moments in the West such as the 1968 student riots in Paris or the global hippie movement promised a moral and cultural revolution which never came. The failures of collective utopia led to individual alienation, a turning inward, trying to leave the world behind.

Ashwani Sharma's (1998) introductory chapter to (Dis)Orienting Rhythms explains how World Music was made to cater to white North American culture. In the late 80’s and 90’s, World Music had emerged as a product for 'vacant white liberal culture' to search for some universal 'authentic', 'human' and 'real' essence. After the political failures of rock and punk music, white music culture needed a new source of ‘realness’ as a response to the urban, technologized, articulate and sometimes militant Black dance music and hip-hop.

To be clear, before World Music there was already a long history of Western-produced music inspired by Oriental culture— that began well before The Beatles, and extends well into the present. But rather than mere exoticisation, World Music claimed to represent a collaboration of equals. Towards the end of the Cold War when global capitalism congratulated itself on its victory over any alternative, World Music offered a utopia of cosmopolitanism and a breaking down of the duality of the West and Third World (or coloniser and colonised).

Multiculturalism and hybridity were celebrated even in the colonised society, but only by those elites that benefited from this contact with the West. Even today, the era of World music is fondly looked back at as a time of 'Incredible India' being re-discovered by the West. Recently, Homegrown uncritically went through the archives to nostalgize about this era when "Western musicians looked to the East for inspiration, and Eastern musicians looked to the West for innovation".

But really, only a certain type of Third World was made visible, and only in a certain way. World music reduced whole national cultures to singular categories, while ignoring the real power differences. Exoticisation works by essentialising a culture, i.e. by identifying some basic, inherent ‘essence’ of a society as representative of the whole society. This tendency follows well before, during and after the colonial project— and is necessary to create a discourse of ‘us vs. them’. Essentializing is a basic social function which allows other cultures to be classified, administered, and appropriated. Examples of this process range from the scale of entire societies being labelled ‘criminal tribes’ to the creation of stereotypes—like the portrayal of ‘spiritual’, ‘authentic’ but ‘dirty’ India.

Of course, any idea of a basic ‘essence’ that is universal to all members of the society is a fantasy that ignores complexity. In reality, there is no ‘innocent’ savage untouched by the corruption of the West— this is a fantasy produced to maintain the apparent opposition and exotic quality of the Orient. The hybrid artist is presented as the miraculous child that finally reconciles the two.

An excellent example of such a reductive process is again provided by Ashwani Sharma is Bally Sagoo's signing on Sony Records. Bally Sagoo is most known for his role in the British Bhangra scene (interestingly a genre that fluidly co-evolved with Black British music like dub and reggae, which is a problem for marketing which tries to keep the exotic separate from the Black). But Sagoo's 1995 album Bollywood Flashback was a strategic move by Sony Records to sell Bombay film music repackaged for white Western consumers (and, in the future, upper middle class and Westernised consumers in the Indian subcontinent). Bollywood remix was aesthetically hybrid, but what was really being sold was the artist's identity as a paratext to the product. Sagoo, Sharma argues, was marketed as a migrant subject who draws both from his 'ethnic traditions' and western knowledge of technology.

In World Music, artists’ identities are portrayed as hybrids of exotic authenticity with Western modernity. They are ambitiously modern despite their traditional background. Artists must perform their nationality and ethnicity. They are put in a box, preventing them from transcending their own cultural position or being considered anything else except their assigned ethnicity. Artists who play 'traditional' i.e non-electric instruments and sing in indigenous languages are preferred by labels and record companies. Specific artists, musical forms and styles are seen as authentic representatives, ignoring the others who have not had the privileging encounter with the West or who don't have photogenic poverty to sell. Thus, those artists who can serve as one-dimensional caricatures of the ‘essence’ of some local culture are given world stage.

World Music reflects a broader fascination with the ‘authenticity’ of the exotic while foregrounding the technological modernity of the West. Artists are forced to self-exoticise in order to be palatable to the Orientalist gaze. Balancing this duality of modernity and tradition forms the basis of the continuum, represented sonically as well as visually.

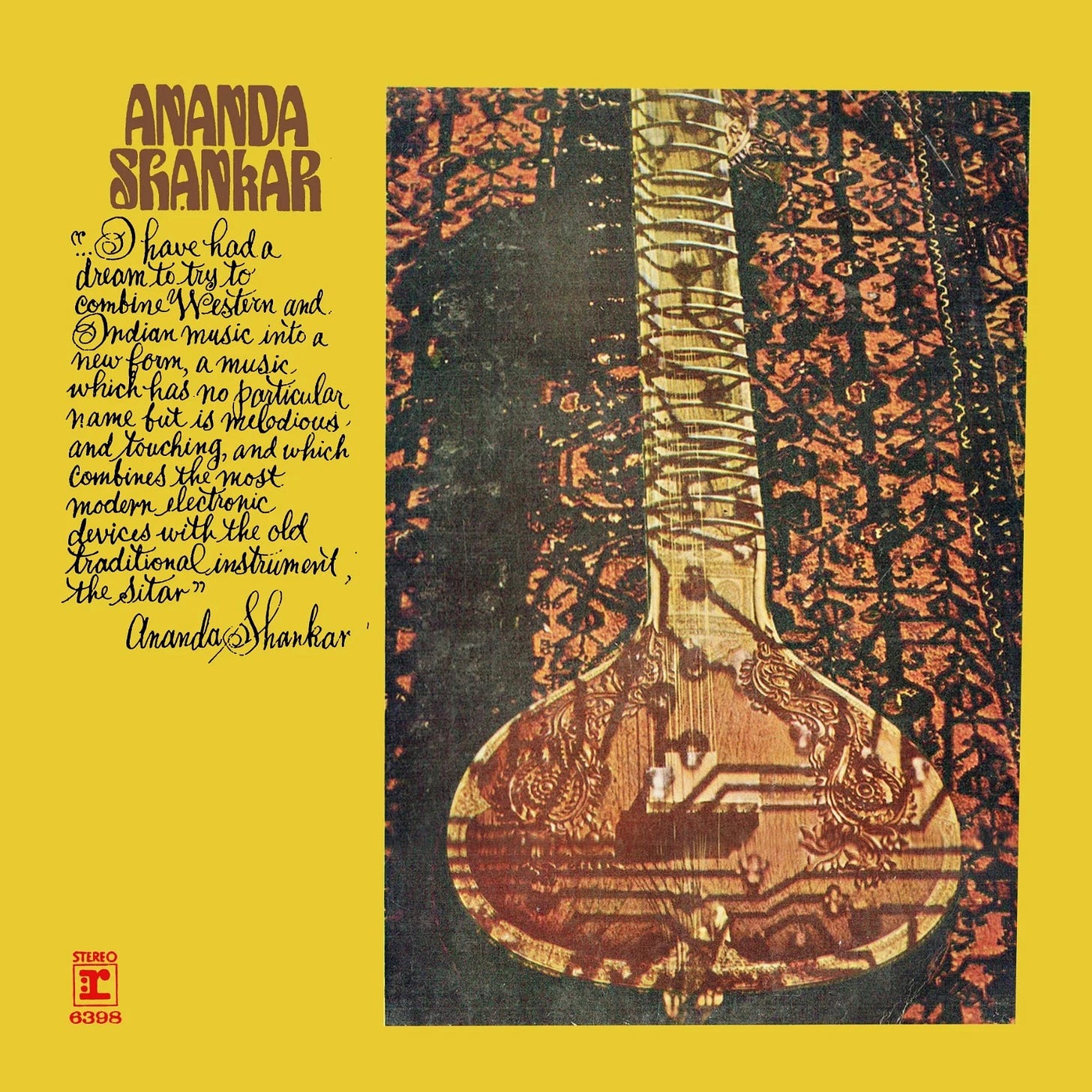

Authentic traditions x Western modernity

At an aesthetic level, desi electronic music is composed of a duality based on the cultural origins of their sounds. This is an immediately recognisable distinction between 'Indian' (traditional sounds, ragas, etc. and 'Western' (beats, bass lines, etc.).

The duality of Indian and Western play distinct functions, with the 'Indian' sound being the source of authenticity, spirituality and heritage and the 'Western' representing the progressive, modern and contemporary. But this is not a meeting of equals. The 'Western' part, which represents modernity, shifts to the background and is taken as a natural, basic requirement to be dance-able. What comes into focus through a fetishistic gaze is the exotic, authentic traditional culture. Even today, Shivhari similarly presents his music as "highlighting the beauty of Indian classical” without “sacrificing” the “groove”, “danciness”, “structure and familiarity” of modern electronic music.

When cultures are reduced to one-dimensional tokens of a supposed basic essence, they are de-politicised and detached from any historical context. This makes them more palatable for appropriation— emptied of meaning and used for fashion.

In World Music, a good example of this tendency is Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's Qawwali music which became a bonafide superstar figure in the genre through remixes and collaborations with electronic producers like Massive Attack. Even today, Qawwali is celebrated as 'enchanting' and 'mystical', but this erases the crucial socio-critical, religious-devotional, and revolutionary elements of the music, reducing it to aesthetic form. The album sleeve of Mustt Mustt (1990) by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan & producer Michael Brook reveals how the music is stripped of its meaning and used only for its sonic quality:

"These are the only two songs with actual lyrics; the rest are classical vocal exercises in which the words have no meaning but are used for the quality of their sound. These notations are selected to fit particular ragas.

‘We made some edits that were not acceptable to Nusrat, because we’d cut a phrase in half —sometimes there were actual lyrics that we made nonsense of.’ A compromise was achieved —important lyrics phrases were restored without losing the musical structure Michael had developed." — Album sleeve of Mustt Mustt (1990), Real World Records (source)

There is a clear power hierarchy here— the authentic local culture of the postcolony is extracted by globalisation and Westernisation. This is a familiar story— of the technological and rationalistic modernity of the West and the authentic traditions and heritage of the Orient.

But it is not a simple story of the old master appropriating the fashions of the savage. Different artists and scenes in the West, in the Third World and in the diaspora mobilize hybrid music towards different ideological ends.

The diasporic Underground and self-exoticisation

Another starting point for tracing the continuum of desi electronic music culture is with the South Asian diaspora (in the West) as its pioneering producers. While World Music offered Western audiences a consumable fantasy of the exotic Other, diasporic South Asian artists in the UK turned this gaze inward, creating hybrid genres that questioned identity, modernity, and cultural authenticity.

Dhiraj Murthy defines 'British Asian electronic music' as a:

“a mix of some of the following: electronic digital manipulation; one or more traditional Hindustani instruments such as the tabla, sitar, sarangi or veena (or samples of them); Asian vocalists; lyrics and samples broadly relating to South Asia; samples of Bollywood tracks, but generally a rhythm line similar to drum and bass; downtempo; jungle; and other electronic musics.”

In the UK, what came to be contentiously called the 'Asian Underground' movement was exemplified by its namesake- Talvin Singh's 1997 historic compilation Anokha— Soundz of the Asian Underground. The Asian 'Underground' was named so for its supposed social and political subversiveness. Since the 80's, South Asian diaspora in the UK had been pushing bold, experimental fusions often with Black British music scenes, ranging from bhangra to dub and jungle and back. These genres aestheticised a feeling of angst amongst minorities in the first world who faced marginalisation and a perceived loss of heritage in the face of cultural assimilation. These scenes connect to a global constellation of culture produced by first and second-generation postcolonial diaspora who struggle for self-expression.

Gayatri Gopinath (2005) initially writes in praise of Asian Dub Foundation, a legendary fusion electronic act known for their political lyricism. ADF mobilized nostalgia for an idea of 'India' that was not based in some ‘essence’ of cultural identity but a shared memory of struggle and defiance against the coloniser. But importantly, Gopinath also points out how tracks like ADF's Rafi's Revenge (1998) problematically reproduce the 'militant masculinity' of icons like Bhagat Singh and Udham Singh and the tendencies of those movements to subordinate others.

For all its claims for subversiveness, the Asian Underground faced the same existential dilemma as other forms of hybridisation— how to represent some shared context of culture and struggle, while avoiding reducing ethnicity to homogenised, empty aesthetics?

So-called ‘underground’ dance music is often called political, even revolutionary, but valid doubts remain. Rafeeq Hasan (2001) describes an all-too-familiar picture of a crowd at a Talvin Singh performance at Fabric, London, as mass of alienated, narcissistic, Black British and Asian hipsters:

"These are not dancers dancing in any sort of modernized scene of tribal collective catharsis, each individual indistinguishable from the next [...] These are atomized individuals, occupying a completely desexualized space, each using unique hand movements to self-stylize themselves, to present themselves [...] as an aesthetic object to be appreciated, though not approached." (205)

Like with any music subculture, there is no guarantee of subversive or socially productive action. Koushik Banerjea (2000) argues that the stale trope of the underground is actually just a place for social visibility, and has nothing to do with any broader political consciousness. Underground diasporic scenes are merely a hipster fashion beginning with the elite, globalised classes of society:

"People for instance who can only appreciate their ghazals or qawwali dipped in junglist wax are no more likely than their peers to accept the growing demands for recognition by Asian working-class folk in the housing, employment and education markets. Rather like those early batch-cooked menus in the original curry houses, it appears to be a case of dilute to taste"

This existential tension between commercialisation and authenticity is obvious and has long been discussed in academia. In the 1920’s, the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany, founded critical cultural studies based in Marxian theory. One of the leading figures of what is now referred to as the Frankfurt School, Theordo Adorno looked at big band and swing jazz to point out the commodification of culture, where art and culture are transformed into products for mass consumption, losing their authenticity and critical potential.

But Rafeeq Hasan makes an interesting point that there is a “subtle subversiveness” on Talvin Singh’s anonymised, self-absorbed, alienated dancefloor at Fabric. Women are, for once, not the object of male gaze. Aesthetically, there is no enforced 'correct way' of dancing regulated by cultural gatekeepers. There is no foreign exotic tribal culture being fetishised and mimicked.

Instead, here is a sense of togetherness built around a 'self-determined style of self-exoticization'. This is an introspective journey which finds authenticity in the self rather than some Other exotic culture. Can this self-exoticisation really be subversive?

These questions are explored in the next part of this series. Until now, we have examined the roots of Indian electronic fusion. This is a history of asymmetry—between the West’s desire for spiritual authenticity and the East’s ambition to be at-par with modernity. From the packaging of ‘exotic’ Indianness for World Music markets to the diasporic search for identity in the Asian Underground, fusion music was shaped by a deep sonic duality: Indian sounds as markers of heritage and mysticism; Western instruments as symbols of progress and futurism. Even when artists reclaimed this hybridity, they often found themselves complicit in the very gaze they sought to subvert. The continuum was born not just of collaboration but of contradiction—a sonic world haunted by the politics of self-exoticisation. In Part 2, we ask what becomes of this lineage once it returns home to India—who inherits it, what it means now, and if and what new futures can still be imagined through it.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Shivhari Shankar for his time and patience with my questions. Thanks also to reviewers: Pranav Manie, Apoorv Somanchi, Sanjana Sheth and others.

No copyright infringement intended. All material credits to the original authors.

References

Banerjea, Koushik (2000), “Sounds of Whose Underground? The Fine Tuning of Diaspora in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Theory, culture & society, 17(3), 64–79.

Gopinath, Gayatri (2005), Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures, Duke University Press,

Hasan, Rafeeq (2001), “The Dialectic of the Dance: On Talvin Singh’s ‘Anokha,’” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 32(4).

Murthy, Dhiraj (2010), “Nationalism Remixed? The Politics of Cultural Flows between the South Asian Diaspora and ‘Homeland,’” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(8), 1412–30.

Schirmann, Kyle (2015), “Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat: Futurism and Pirate Modernity in South Asian Electronica,” Master’s Thesis, New York: Columbia University.

Sharma, Ashwini (1997), “Sounds Oriental: The (Im)Possibility of Theorizing Asian Musical Cultures,” in Dis-Orienting Rhythms: The Politics of the New Asian Dance Music, ed. Sanjay Sharma, John Hutnyk, and Ashwini Sharma, London; New Jersey: Zed Books,

This is great work man! Enjoyed reading every bit of it.

Love this